The global oil market looks well-supplied at the end of the year, with output sufficient to absorb a supply disruption in Venezuela, the world’s biggest crude resource holder.

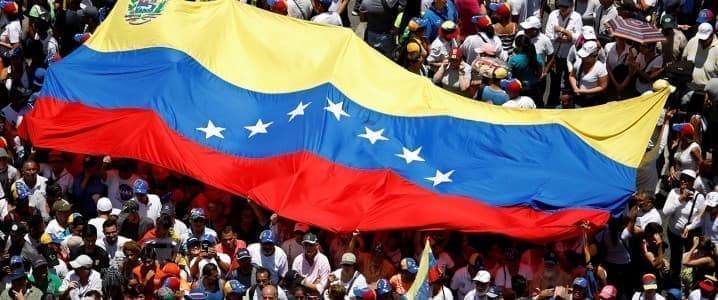

The escalating U.S.-Venezuela tensions in recent weeks, a tanker seizure, and further U.S. sanctions squeezes on Nicolas Maduro and his allies, including companies operating tankers, have cut Venezuela’s production to a seven-month low.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimated Venezuela’s oil supply at 860,000 barrels per day (bpd) in November, down from 1.01 million bpd in October and a similarly above 1-million-bpd level in September, when

Venezuelan crude oil output hit its highest since February 2019.

Further declines in Venezuela’s oil supply are expected in December, following the U.S. actions in Caribbean waters. After seizing one tanker carrying Venezuelan crude early this month, the U.S. is prepared to seize more tankers, Reuters reported last week, citing unnamed sources who said there was already a list of vessels targeted for seizure.

Whatever the end-game of the U.S. in Venezuela will be, falling oil supply from Venezuela is unlikely to affect the global market too much, as the current oversupply would represent a comfortable cushion to absorb a few hundred thousand barrels of crude per day off the market.

In the worst-case scenario for Venezuela’s crude supply, with additional restrictions and a shortage of diluents to help the heavy crude flow for exports, Venezuela could lose up to 500,000 bpd of its oil production, according to Reuters estimates cited by columnist Ron Bousso.

Venezuelan Scenarios

Venezuela is one of the wild cards on the global oil market as we head into 2026, as uncertainties abound regarding a potential U.S. incursion and how such a move would impact production.

A loss of Venezuelan oil production in case of a U.S. military intervention will materially impact global benchmark prices as the market will have to replace Venezuela’s heavy crude—the bulk of Caracas’ crude exports, according to Rystad Energy.

If the U.S.-Venezuela tension escalation into a U.S. incursion in the South American country, this volume of crude would be at risk, depending on the scale of military activity, the energy intelligence firm said.

“Although the volume is small in terms of global trade flows, the quality is unique as over 67% of the output is heavy,” Rystad Energy noted.

Related: PDVSA Faces Pricing Pressure as Tanker Seizure Disrupts Crude Flows

As a result, the overall tightening of the global heavy market would boost the prices for the heavy grades that the U.S. imports, especially the Canadian heavy crude grades. A temporary loss in Venezuelan production is also expected to push up the price of the sour Dubai benchmark against ICE Brent as Asia will scramble to replace the lost Venezuelan barrels, according to Rystad Energy.

Canada’s heavy oil, the heavy grades produced in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico, and Colombia’s Castilla, Apiay, Magdalena, and Mares blends could replace losses of Venezuela’s flagship super heavy grade Merey.

Still, it’s not certain that U.S. President Donald Trump would necessarily pursue regime change or an incursion of some kind in Venezuela. But it’s certain that any regime change of Maduro could be a game-changer for oil production in Venezuela, U.S. access to Venezuela’s heavy crude fit for U.S. Gulf Coast refineries, and America’s influence in the Western Hemisphere and Latin America.

Escalating tensions could lead to a short-term squeeze in Venezuela’s supply, but a regime change away from Maduro could lead to easing of the U.S. sanctions, renewed foreign participation, and an increase in Venezuela’s crude oil production.

“It is not clear that the US will push for regime change in Venezuela, or how such an attempt might play out if it did,” energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie said earlier this month.

If sanctions were lifted and the desperately needed operational and financial support became available for Venezuela, it could have a significant impact on the country’s production, in both the short and long term, WoodMac’s analysts say.

Improved operational management could result in quick increases in production, according to Adrian Lara, Wood Mackenzie’s principal analyst for Latin America upstream.

“Our assumption is that there are a lot of wells that just need a workover,” Lara says. “You can boost production through opex, without needing much new capex.”

If favorable conditions exist, operational improvements and some modest investment in the Orinoco Belt could raise Venezuela’s production back to the levels of the mid-2010s at around 2 million bpd within one to two years, WoodMac reckons.

Before any boost occurs, Venezuela – and the global oil market – will have to contend with lower Venezuelan supply in the coming weeks and months. That’s not necessarily a bad thing in what many analysts believe would be a badly oversupplied market, especially in the first quarter of 2026.

Due to expectations of a large oversupply, most investment banks expect Brent crude prices to average below $60 per barrel next year, with WTI prices even lower.

By Tsvetana Paraskova for Oilprice.com

More Top Reads From Oilprice.com