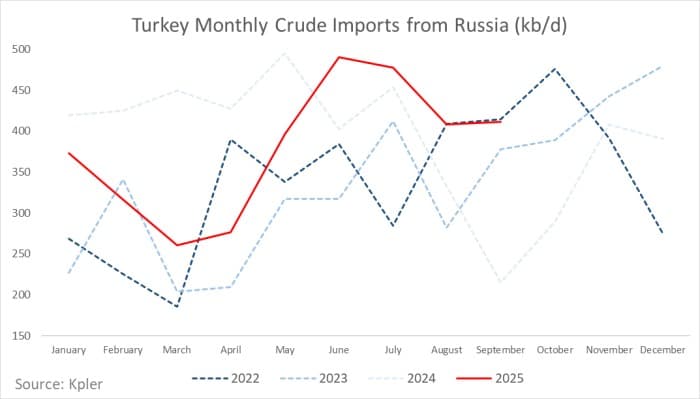

Midway through autumn 2025, Russian crude oil continues to dominate Turkey’s refinery feedstock, defying both geopolitical pressure and the Trump administration’s assertive diplomacy. September import data show Russian volumes flowing to Turkey above monthly averages at 410,000 b/d, extending a pattern that began in early summer and shows little sign of reversing.

On 25 September, when US President Donald Trump met his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdo?an at the White House for the first time in six years, the conversation predictably turned toward energy. Trump urged Ankara to curb its imports of Russian oil – a politically charged message delivered at a time when Turkey’s dependence on Moscow’s barrels is at a four-year high. Yet the Turkish government quickly deflected any responsibility. The country’s energy minister reminded the press that crude procurement is a “commercial decision made by private refining companies”, and not a matter of state policy. Turkey’s refiners – the state-controlled Tüpra? (Türkiye Petrol Rafineleri A.?.) and Azerbaijan’s Socar-owned Star Rafineri A.?. – are the backbone of Turkey’s energy system and the principal buyers of Russian Urals crude.

Since the start of summer 2025, Russian crude imports to Turkey have averaged around 410,000 b/d, roughly 20% higher year-on-year. The reason lies as much in refinery design as in economics. Turkish refineries were built to process heavier, sour grades such as Russia’s Urals – a crude with a 29–30 degrees API gravity and higher sulphur content than lighter Middle Eastern or U.S. grades. Urals isn’t the only sour crude available in the Mediterranean market but finding a viable substitute that matches both quality and price has proven difficult. The challenge has only grown since a series of Ukrainian drone strikes disrupted operations at Russian refineries, curbing domestic throughput and pushing more Urals crude onto export routes. Russia’s seaborne exports have surged to 3.4 million b/d, the highest level since the spring of 2024 – a wave that Turkey, among others, has eagerly absorbed. In the first week of October alone, five Russian tankers arrived from Primorsk and discharged cargoes at Turkish oil terminals.

One theoretically promising substitute is Iraq’s Kirkuk crude, a heavy grade now flowing back to the market after a two-year pause. Iraq recently restarted northern exports to Turkey, potentially offering regional refiners an alternative to Russian barrels. The oil passes through the Kirkuk–Ceyhan pipeline, carrying 400,000–450,000 b/d before its 2023 shutdown. Current plans call for only 190,000 b/d to be sent to Iraq’s state marketer SOMO for export via Ceyhan, with an additional 50,000 b/d reserved for domestic use in the Kurdish region. But Kirkuk’s comeback faces challenges. SOMO intends to sell Kirkuk at the official selling prices, meaning they would be priced at a premium to Brent ($1.25 per barrel in October). Faced with difficulties in selling the first Kirkuk cargoes from Ceyhan, this might be too optimistic as reported spot prices have been more than $1 per barrel below Brent. Moreover, even if flows rise, refiners note that Kirkuk’s volatile quality make it a supplement, not a replacement, for Urals.

Another potential feedstock, Kazakhstan’s Kebco (similar in specification to Urals), is not under EU sanctions and thus commands strong demand across the Mediterranean. But that popularity carries a cost: Kebco trades at a $2.75-per-barrel premium to Dated Brent, compared with an assumed Russian Urals’ $7-per-barrel discount as of early October. Price alone ensures that Russian barrels remain hard to resist. While the return of Kirkuk has diminished Kebco’s premium slightly, market watchers attribute the shift more to expectations of higher Urals supply than to Iraq’s renewed presence. For refiners squeezed by narrow margins, Russian crude still offers the most attractive economics – even amid political risk.

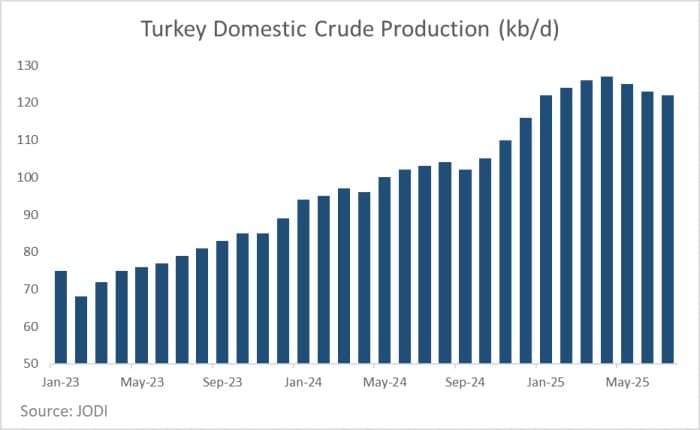

Complicating the picture further is Turkey’s own rising crude production. Newly discovered oilfields – ?ehit Esma Çevik (SEC) and ?ehit Aybüke Yalç?n (SAY), announced in 2022 and 2023 – have lifted national production from 70,000–75,000 b/d in early 2023 to 120,000–125,000 b/d in 2025. Unlike Turkey’s traditional output, a 12 degrees API ultra-heavy crude, the new fields produce a lighter Gabar grade of 40 degrees API, significantly improving the quality of domestic supply. But there’s a catch. Turkish law prohibits the export of domestically produced crude, meaning all output must be refined at home. And since Turkish refineries are configured for heavier blends, lighter domestic oil needs to be blended with heavier grades – most conveniently, Urals. In effect, Turkey’s rising production reinforces (rather than reduces) its reliance on Russian feedstock.

The new fields also carry geopolitical baggage. Both SEC and SAY are located in the restive Kurdish southeast, a region long marred by insurgency and instability. Yet production has been steady, and the oil must find its way into the domestic system – blending Turkish light and Russian heavy crudes in a marriage of necessity. Turkey’s position illustrates the collision of politics, economics, and refinery configuration. Washington’s calls to curtail Russian oil imports may resonate diplomatically, but they clash with the realities of Turkey’s refining infrastructure and cost structure. Alternative supplies – whether from Iraq, Kazakhstan, or the domestic market – remain either too expensive, too limited, or too light to fully displace Urals. As of early autumn, with imports above average and Russian crude still offering the best value per barrel, Ankara shows no urgency to change course. For all the political heat surrounding its choices, Turkey’s energy calculus remains coldly pragmatic: in a world of heavy blends and light politics, Russian oil still fits the Turkish outlook best.

By Natalia Katona for Oilprice.com

More Top Reads From Oilprice.com: