Dawn was breaking over the Amazonian city of Belém on Saturday morning, but in the windowless conference room it could have been day or night. They had been stuck there for more than 12 hours, dozens of ministers representing 17 groups of countries, from the poorest on the planet to the richest, urged by the Brazilian hosts to accept a settlement cooked up the day before.

Tempers were short, the air thick as the sweaty and exhausted delegates faced up to reality: there would not be a deal here in Brazil. The 30th UN climate conference would end in abject failure.

The sticking point was fossil fuels. As science has told us for well over a century, the carbon dioxide that burning them produces is heating up the planet, now to dangerous levels.

But in more than 30 years of annual climate meetings, the need for that to halt has been mentioned only once – in a resolution made two years ago, at Cop28 in Dubai, to “transition away from fossil fuels”. Delegates from the Arab Group of 22 nations, from Russia, and from a sprinkling of others, were determined it would not happen again.

A growing number of countries, however, were equally determined that progress on this was urgently necessary. They had come up with a plan, which was gathering more and more support, and they made it clear they were prepared to dig in.

Meanwhile, developing countries desperately wanted to move forward on securing the money that would help them cope with the already disastrous impacts of extreme weather.

By the early hours of Saturday, some delegates were ready to walk out and force a collapse. “It was on the edge for us,” said Ed Miliband, the UK energy minister. “I was prepared to walk away.”

The breakthrough, when it came, was with Saudi Arabia. Soon after 6am, Miliband and the EU climate commissioner, Wopke Hoekstra, split from the main group to hold a private conversation with the chief Saudi negotiator, Khalid Abuleif. They pressed on him wording that would obliquely recognise the global commitment to “transition away from fossil fuels” made two years ago in Dubai. Rather than explicitly namecheck fossil fuels, it would refer to “the UAE consensus”, the name given to the Cop28 deal.

Khalid agreed to take it away and reflect. Ministers around the room held out little hope – Saudi had been obdurate all night.

An hour later, he returned. To great surprise, the wording was accepted. The room collapsed into relief. Applause rang out. The deal was done.

With the “Belém political package”, the world took another small step towards the phaseout of fossil fuels – a faltering, inadequate step, and one that will barely interrupt the climate’s steady march towards catastrophe. But a significant departure from total inaction nonetheless.

Alongside the oblique commitment in the legally agreed text of the deal, countries will begin work on a roadmap to phase out fossil fuels, but this will be largely a voluntary initiative, led by Brazil, that will report back next year. Addressing the cuts in greenhouse gas emissions needed in order for the world to stay within the 1.5C limit was also put off to next year. Developing countries secured a tripling to $120bn of annual finance to help them adapt to the impacts of extreme weather, but that sum will not be delivered in full until 2035. Workers will benefit from a “just transition mechanism” to help people working in high-carbon industries to shift to the clean economy, but commitments to include “critical minerals” – needed for renewable energy components, but whose extraction has been dogged by human rights abuses – were excised, at the behest of China and Russia.

As the world teeters on the brink of climate “tipping points” that could destroy ecosystems and plunge whole regions into chaos, it was not the “giant leap” needed. “Cop30 gave us some baby steps in the right direction, but considering the scale of the climate crisis, it has failed to rise to the occasion,” warned Mohamed Adow, director of the Power Shift Africa thinktank.

This flawed deal might have been all that was possible, given the geopolitical headwinds – a US president who shunned the talks and is wedded to oil and coal, the rising tide of rightwing populism, conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, intolerable levels of inequality, and global economic uncertainty.

“The climate arsonists – the fossil fuel giants – were finally in the crosshairs at Cop30,” says Louise Hutchins, convener at the Make Polluters Pay coalition. “There is no turning back on that. The political space is open. Now we must turn it into a real fire escape to a safer world.”

But while nations were able to applaud the gavelling through of the deal, Cop30 also revealed deep fissures in the only global process for tackling the climate crisis. “Cops are consensus-based, and in a period of geopolitical divides, consensus is ever harder to reach,” said António Guterres, the UN secretary general. “I cannot pretend that Cop30 has delivered everything that is needed. The gap between where we are and what science demands remains dangerously wide.”

If the world is to avoid the worst ravages of climate breakdown, the UN climate talks alone will not be nearly enough.

In search of a roadmap

When Brazil set out to host Cop30, it had one key objective: to “send a strong signal that multilateralism is working”. Multilateralism means taking a global approach, seeking collective action to solve pressing problems. The UN framework convention on climate change, signed in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, is one of the few remaining multilateral enterprises, acknowledging that all countries have an equal say in the future of the planet, the poor and vulnerable as much as the rich who historically caused the problem.

But around the world, this equitable approach is faltering. Trump rejects all forms of it, preferring to strike his own deals with favoured nations and issue tariffs and other threats seemingly on a whim. He has taken the US out of the Paris climate agreement for a second time and, though still entitled to take part in the annual talks, the US sent no delegation to Cop30.

The absence was constantly felt. At first, the conference halls buzzed with the worry that the US would take the bullying approach – “thuggery”, was how Andrew Forrest, the Australian billionaire, described it to the Guardian – that forced small countries to back down on a hoped-for carbon levy on shipping at International Maritime Organisations talks this autumn.

In the end, the US did not interfere in any overt way at Cop30. Perhaps it did not need to: Saudi Arabia, an ally of Trump, was an effective blocker.

All countries agreed to “transition away from fossil fuels” at Cop28 in 2023, which was presided over by an oilman – Sultan Al Jaber, the head of the United Arab Emirates’ national oil company, Adnoc. Perhaps only an oil executive could have pulled off the coup that was including fossil fuels in the text. Yet as soon as that commitment was signed, some countries sought to unpick it, with Saudi Arabia claiming it was only one of a menu of options, and by the time the next Cop rolled round – in another dictatorship dependent on oil exports, Azerbaijan – the petrostate had marshalled allies to ensure attempts to build on the resolution failed.

For some, that should have been the end of the story. One negotiator from the Middle East told the Guardian: “The [resolution] was passed at Cop28. We should not need to return to it. Now it is for every country to interpret it in their own circumstances – bringing it up again at Cop is trying to impinge on national sovereignty.”

Those in favour of the phaseout, however – including scientists, who have said clearly it is needed if the world is not to stray further into the climate danger zone – argued that the “UAE consensus” was only a first step. At Cops, it is common to agree a step forward in principle one year, and then in future years “operationalise” the commitment through an agreed course of action.

The way forward, many experts decided, was for a “roadmap” to the transition to be drawn up. Johan Rockström, professor of earth systems sciences at the Potsdam Climate Institute, said: “The truth is that our only chance of keeping 1.5C within reach is to bend the global curve of emissions downward in 2026 and then reduce emissions by at least 5% a year. [That] requires concrete roadmaps to accelerate the phaseout of fossil fuels and protection of nature.”

Such a roadmap would have to be approached delicately in order to keep every country onboard. It would have to be open to all, but contain nothing that would force any country to act or set timetables for their fossil fuel production or use. Everything would be voluntary. Laurence Tubiana, an architect of the Paris agreement, now chief executive of the European Climate Foundation, dismissed claims from oil-producing countries that such a process would infringe their national sovereignty. “Every country has to imagine for itself what policies they want, what role they have to play, and what ambition they have,” she said.

Long before Cop30, more than a year ago, Brazil had already set out its intention for a phaseout of fossil fuels, in its national climate plan under the Paris agreement, known as a nationally determined contribution (NDC).

The linchpin was Marina Silva, Brazil’s charismatic environment minister. Ahead of Cop30, she expressed support for a phaseout, and took the idea to the UN general assembly in September. It was at her urging that Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, referred to a phaseout at least three times during the summit, while she addressed several high-level ministerial meetings on the subject. In an exclusive interview with the Guardian during the first week of Cop30, she urged all countries to find the courage to make the move.

But Lula holds together a fragile coalition government. Itamaraty, Brazil’s foreign ministry, was known to be against commitments on fossil fuels, preferring to emphasise the country’s newfound role as a major oil and gas exporter. And Silva was not made president of the Cop talks, as some had expected. Instead, that job went to André Corrêa do Lago, a veteran diplomat. Tall, handsome and genial, do Lago is much admired among fellow negotiators. He joked with them during the first week of the talks that the sessions should be considered “therapy”, and invited them to send him “love letters” expressing their negotiating positions. But no one gets through two decades of Cops without a core of steel, and do Lago has been, nearly his entire career, an Itamaraty man.

Though do Lago insisted to the Guardian that he “hoped” a fossil fuel phase-out could be included, some people within the negotiations tell a different story. “He was against the fossil fuel phaseout being on the agenda, being in the text, throughout,” one insider told the Guardian. “It was do Lago who wanted it out [of the text],” said another delegate. “He only listened to the Arab Group,” said a third. He was accused of overstating the opposition to text on the phaseout, and trying to railroad through text with fossil fuel commitments excised.

Do Lago told the Guardian he had tried hard to retain wording on the transition away from fossil fuels in the text. “It is incorrect to say I did not want it,” he told the Guardian after the conclusion of Cop30. “I not only wanted it, I put it in there. This was President Lula’s very clear message. But unfortunately, my job as president to have a document that can fly. I can’t propose something that I know is dead from the start.”

He said “a large number of countries’ had made known they would not accept it. “This is the problem with consensus,” he said. “Everyone has a veto.”

Aware of Brazil’s divisions, supporters of the phaseout had spent months quietly recruiting developing countries to their cause. Colombia was the originator, but others including Kenya, Sierra Leone and even oil-rich Nigeria came onboard, as well as the coal-dependent Philippines, and coal-producing Mongolia. The European Union, once a leader on climate action, was less clearcut and ministers arrived in Belém without an agreed position, but came onboard with a bang in the second week.

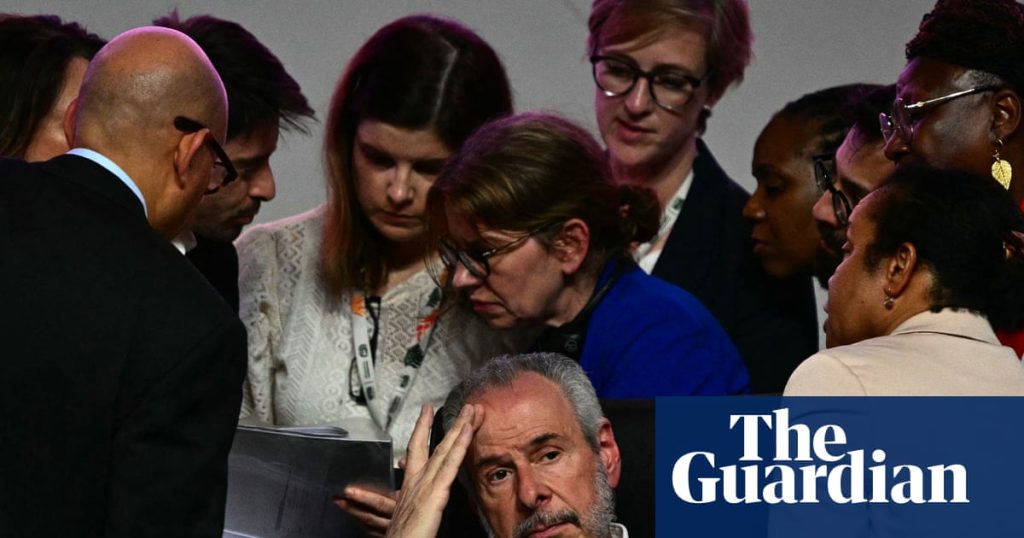

The following day more than 80 countries issued their call for the roadmap in a dramatic intervention. More than 20 ministers crowded the platform, standing in two rows as Tina Stege, climate envoy of the Marshall Islands, exhorted: “Let’s get behind the idea of a fossil fuel roadmap, let’s work together and make it a plan!” NGO Greenpeace described the event as “the turning point” of the conference.

But the Brazilian presidency remained downbeat on the plan. Though he told the Guardian that the divide over the issue could be bridged, do Lago kept insisting 80 countries were against the plan, though these figures were never substantiated. One negotiator told the Guardian: “We don’t understand where that number comes from.”

A clue came when Richard Muyungi, the Tanzanian climate envoy who chairs the African Group of Nations, told a closed meeting that all its 54 members aligned with the 22-member Arab Group on the issue. But several African countries told the Guardian this was not true and that they supported the phaseout – and Tanzania has a deal with Saudi Arabia to exploit its gas reserves.

In the short time remaining – just three days to go before the official deadline of Friday evening – delegations worked feverishly behind the scenes. China, having demurred on the issue, indicated it would not stand in the way; India also did not object. The anti-roadmap position crystallised: Saudi Arabia, the Arab Group and Russia were the prime movers, steadfastly blocking any mention of the roadmap.

An early draft of text that would be the main outcome of the conference included wording on the phaseout. It was replaced on Wednesday with a new draft that removed it. In response, as the Guardian revealed, 29 countries wrote to the presidency late on Thursday night – just hours after a fire in the conference centre forced a full evacuation – all but threatening a walkout if the issue was not included in the text.

By then, however, it was very late in the Cop process. Typically, big ideas need months, if not years, of careful preparation, floating the concept, gathering allies, working out where obstacles lie, wooing neutral countries. Attempting to foist a whole new idea on to the agenda in the late stages was regarded by some as unacceptable – one person close to the Arab Group told the Guardian the Cop had been “hijacked”.

At 5pm on Friday, the presidency called ministers into its offices for the final take-it-or-leave-it talks. At that point, the text was barren of references to fossil fuels in any form, and movement was looking almost impossible. Cop veterans settled in for a long night.

A political compromise

While ministers were stuck in the sweaty conference room in the Brazilian presidency’s private suite within the sprawling Cop30 complex, thousands of miles away in Johannesburg a separate set of meetings was taking place. South Africa hosted this year’s G20 talks, which coincided with the final hours of Cop30.

Brazil’s Lula da Silva, fresh from an appearance in Belém, used his meetings with world leaders in South Africa to push for a stronger settlement at Cop30. His key goal was the pursuit of a side deal with the EU that would transform the outcome of the climate conference for the developing world. Lula’s charm won the day – the EU made a U-turn on the key issue of adaptation.

Developing countries’ central demand at Cop30 was a tripling of the finance available, from publicly funded developed country sources, to help them adapt to the impacts of extreme weather. Adaptation is now crucial: some countries are already spending up to a 10th of their national budgets on coping with the impacts of droughts, floods and storms, soaking up money they could otherwise spend on health, education or public services.

Only a few days earlier, a senior EU minister had told the Guardian that the tripling was not going to happen. But when Lula spoke to Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, the immovable became a possibility.

Even a tripling to $120bn falls far short of the $300bn a year developing countries are estimated to need by 2035, and countries were denied the 2030 deadline they wanted – as well as for the money to be additional to the $300bn in public funds developed countries have already promised. Syeda Rizwana Hasan, Bangladesh’s environment adviser, said: “The tripling is a political compromise position, not one that displays the urgency required.”

Within the final text, the commitment is couched in slightly ambiguous language: the text “calls for efforts” rather than insists on the tripling. But developed and developing countries have assured the Guardian that they regard it as a firm target, and for many campaigners it was a highlight amid otherwise frustrating talks.

This compromise on adaptation funding, according to several insiders, was a spur to Saudi Arabia agreeing the final Cop30 text. The kingdom feared looking isolated, and being blamed if the talks collapsed. At 7.15am on Saturday, Khalid finally agreed that a reference in the text to “the UAE consensus” – an oblique nod to the “transition away from fossil fuels”, which was the key part of that consensus – could be retained.

‘A roadmap to a roadmap’

A legal text that refers only obliquely to the “transition away from fossil fuels”, and a non-binding side agreement to report back to a future meeting on a forum to discuss an eventual phaseout – a “roadmap to a roadmap” as one campaigner put it – may sound like a dangerously weak deal.

But many observers and parties to the talks told the Guardian that the roadmap idea would dominate future Cops. And the convoluted Cop process can be its own strength – the report that is produced on the roadmap could be “adopted”, “recognised” or “welcomed” by a future Cop, giving it legal standing within the process.

Claudio Angelo, the head of international policy at Brazil’s Observatorio do Clima thinktank, said: “This conversation has become inevitable, and we must ride this wave now.”

“A week before this Cop kicked off, the idea that a hugely diverse group of over 80 [developed and developing] countries would actively push for a formal way forward on the global phaseout of fossil fuels was right at the limits of even the most optimistic expectations,” added Leo Roberts, of the E3G thinktank. “Of course the best outcome [would have been] a formal universally agreed text. But the signal from this Cop is clear: a big and growing number of countries recognise that a managed, collectively navigated route to fossil fuel phaseout is preferable to the chaotic absence of planning we currently have. The Cop is finally showing it can be a place in which the transition away from fossil fuels can be openly discussed. You can’t put that back in the box.”

Outside the windowless negotiating rooms of the sclerotic UN process, the real world is moving fast. Renewable power surpassed coal this year, and investment in clean energy, at $2tn a year, is now double that going into fossil fuels, according to the International Energy Agency. More than half of China’s power generation capacity is now low-carbon, and half of its new cars electric. India has met its renewable targets five years early, solar panels this year became Pakistan’s largest power source, and at last Africa – with the world’s biggest capacity for solar generation, but long overlooked when it came to investment – is seeing a surge.

For many, it is this progress in the real economy, rather than the negotiations, that is now the major source of hope. Al Gore, the former US vice-president and veteran climate campaigner, pointed to the revolution already under way. “Just as we have passed peak Trump,” he said, “I believe we have also passed peak petrostate. They may be able to veto diplomatic action, but they can’t veto real world action… the rest of the world is fed up with delay and denial.”