The Caribbean’s slavery reparations body has decried misleading press reports that suggest their aim is to “break the British Treasury” by demanding trillions of pounds, as they call for a mutually beneficial restorative justice programme.

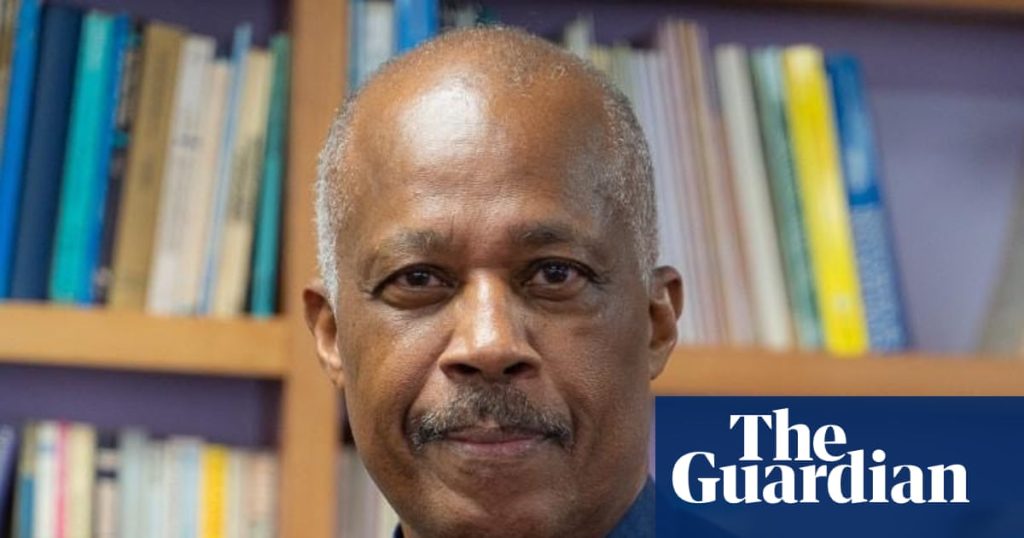

Prof Sir Hilary Beckles, chair of the Caricom Reparations Commission (CRC), which was set up to progress the Caribbean’s pursuit of justice for centuries of enslavement and colonisation by European nations, made the comments during the body’s first official visit to the UK.

In a press conference on Tuesday he said the conversation and debate around reparations was important, but stressed that it was critical to raise awareness of the enduring harm caused when African people were kidnapped, enslaved and oppressed – and when Caribbean countries were later left, after independence, “with no resources, bankrupt treasuries [and] no economic strategies”.

“We have spoken historically about how Britain has extracted wealth from our societies, our communities … All dimensions of our civilisation have been subject to severe extraction of wealth that has helped to build out the institutions of this country and to build up the nation that is Great Britain today,” he said, adding that the Caribbean was not “seeking to offer the same extractive agenda”.

The reparations movement, he said, was about collaboration between former colonies and former colonisers, justice for crimes committed against humanity, and reparations for the resulting human suffering that still persisted today. It was about cleaning up the “mess” left by colonialism “so that we can all go forward together”, he said.

Speaking at a lecture in London on Monday, he said the CRC’s ultimate aim was for the UK and its former colonies to identify “mutual strategies for mutual benefits”.

“Every week, we open the newspapers and we hear the most terrible things about these reparations people from the Caribbean. Some have said that we have come here to break the British Treasury by demanding millions and billions and billions of pounds. And they have consistently tried to discredit what is an ongoing moral and ethical argument for justice, the right to justice,” he said.

During the lecture, Sir Beckles pointed to the consequences of enslavement, which continue to hamper the Caribbean’s development, including unfair debt accumulation, health and education challenges, and the struggle to build the resilience needed to face worsening natural disasters.

This week, he is a leading six-member CRC delegation, which has been meeting with UK parliamentarians, Caribbean diplomats, academics and civil society groups to “raise consciousness, provide information to the public, provide historical knowledge and contemporary understanding” and facilitate a future dialogue between Caribbean and British governments.

Between the 15th and the 19th century, more than 12.5 million Africans were kidnapped, forcibly transported to the Americas and sold into slavery.

Caribbean governments have been calling for recognition of the lasting legacy of colonialism and enslavement, and for reparative justice from former colonisers, including a full formal apology and forms of financial reparations, such as debt cancellations.

David Comissiong, ambassador to Caricom and vice-chair of the Barbados National Taskforce, told reporters on Tuesday that “the overburdened debt situation” facing many countries in the region resulted from centuries of European nations siphoning off and plundering Caribbean resources.

This, he said, was linked to modern-day challenges facing the Caribbean, such as dealing with the climate crisis.

“If we don’t, with proper goodwill, and the understanding that we are all in this together … address these lingering situations of injustice and fragility, then what happens? The climate crisis only gets worse. Developing countries only suffer more because they don’t have the resources to respond. The climate refugee situation only worsens.

“Yes, we are looking for justice for ourselves. But by seeking justice for ourselves, we are also seeking universal justice. We are also seeking to cure and to heal wounds and inequities and unsustainability … [that] will wreak havoc not only on us but will wreak havoc on our entire world,” he said.

The region is part of a growing global movement for slavery reparations. At the ongoing UN Cop30 climate conference in Brazil, hundreds of human rights groups and environmentalists have urged delegates to put reparations on the agenda.

In their open letter they argued that “global warming began with the industrial revolutions that were made possible by the resources provided by imperialism, colonialism and enslavement, [and] that colonialism and enslavement skewed the global economy in favour of the material and financial interests in the global north”.

The issue was also prominent when Commonwealth leaders met last year. At a summit, Britain’s prime minister, Keir Starmer, said the slave trade was abhorrent but that countries should be “looking forward” and addressing current challenges such as the climate crisis.

But the UK was among the leaders who issued a statement saying that “the time has come for a meaningful, truthful and respectful conversation towards forging a common future based on equity”.