The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has decided to postpone the adoption of its Net-Zero Framework (NZF) for another year. This delay, while creating additional uncertainty, warrant careful examination of the proposed mechanisms. The delay will now give member states time to refine ambiguous or contentious elements to produce a stronger, more implementable framework.

The Rystad research revealed a substantial disparity between projected clean-fuel availability and targeted demand, exacerbated by infrastructure constraints, which raises concerns about the feasibility of the prescribed transition timeline. Furthermore, the study exposed a persistent imbalance in the carbon-trading mechanism, with demand for Tier II remedial unit offsets expected to outstrip available surplus units through 2035. This structural deficit is anticipated to drive trading prices towards the Tier II penalty ceiling.

The research also underscores the need for careful consideration in designing the reward mechanism to prevent it from becoming a mere penalty-collection system. While the cost gap is expected to narrow as technology matures and economies of scale are achieved, a well-designed reward mechanism is crucial to incentivize sustainable practices. By addressing these critical issues, the IMO can develop a more effective and equitable NZF, ultimately supporting the global shipping industry’s transition to a low-carbon future.

“Decarbonizing the maritime sector is a complex challenge that goes beyond shipping, closely tied to the global shift from fossil fuels to renewables,” said Junlin Yu, vice president of supply chain research, Rystad Energy. “Our findings suggests progress will likely lag behind the IMO’s current expectations due to infrastructure limits, technology readiness, and energy system interconnections. While the industry is committed, practical constraints demand a realistic approach. The IMO should use the extra year to refine the NZF into a more practical and equitable framework.”

Rystad Energy recently published a detailed investigation into the NZF and its financial implications for the shipping industry’s decarbonization journey.

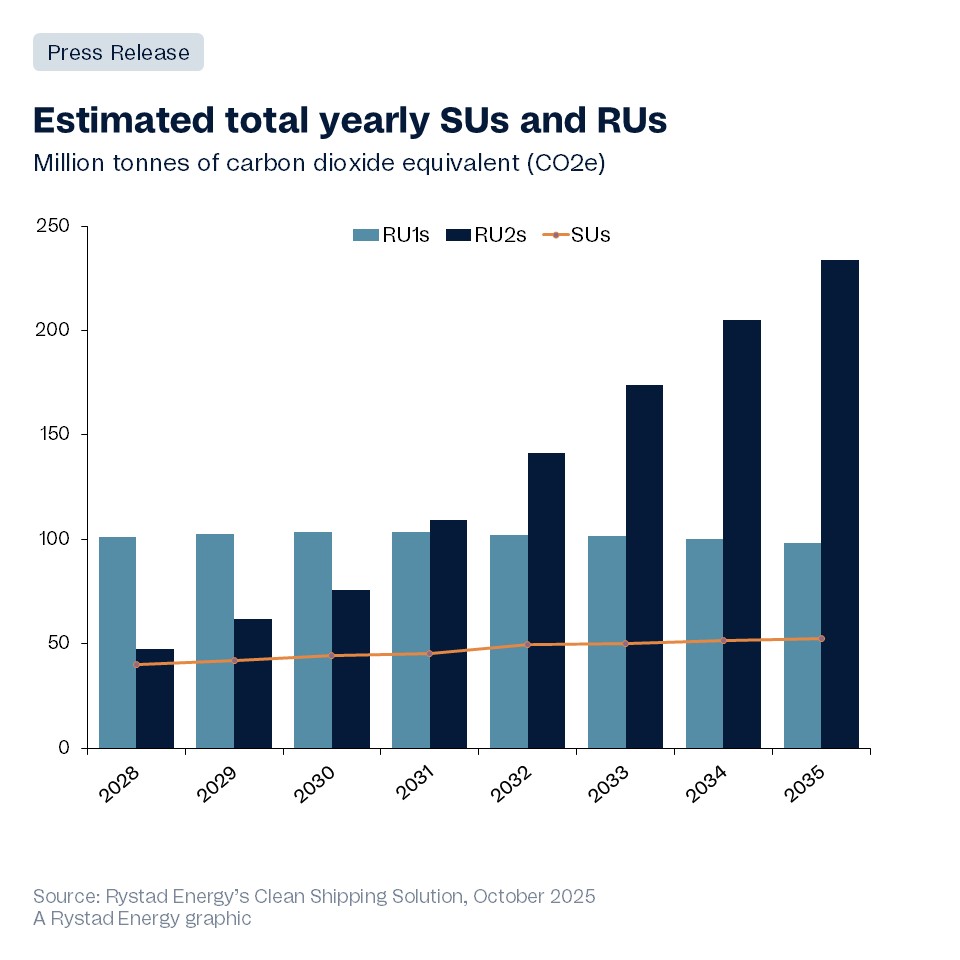

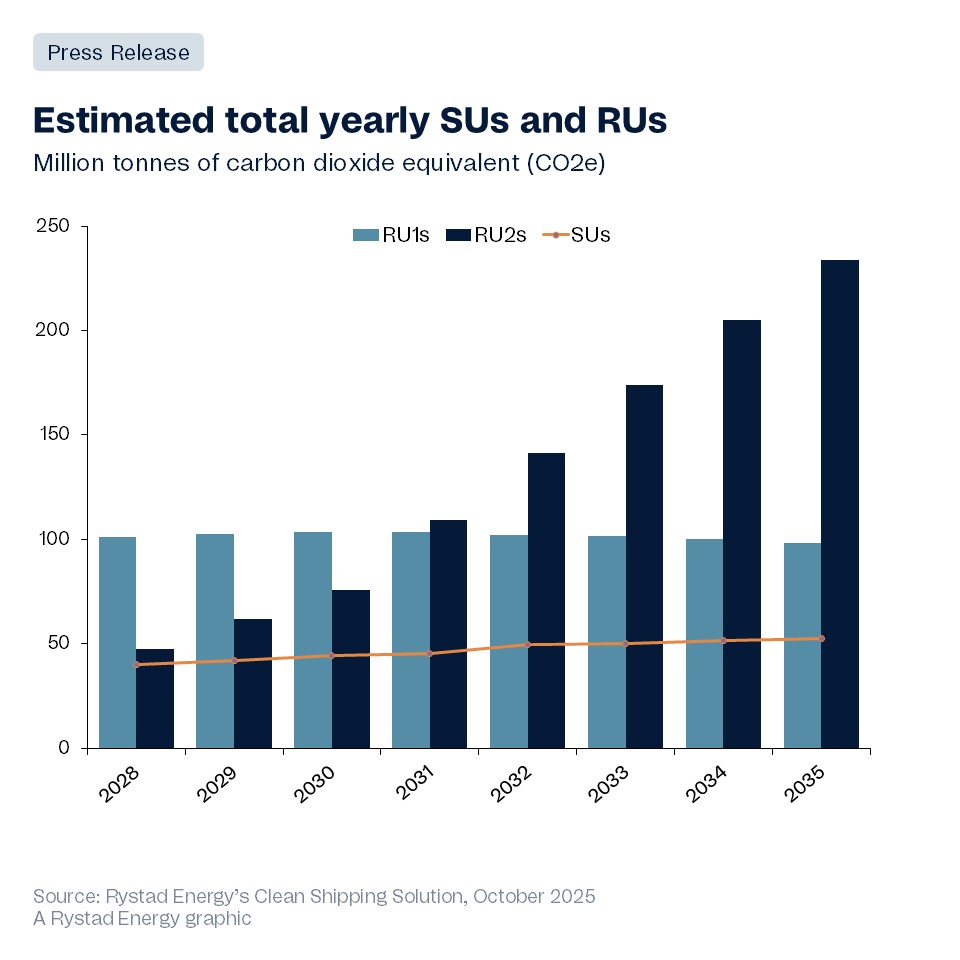

Under the NZF, vessels that meet the direct target may generate Surplus Units (SUs), while non-compliant vessels will generate Remedial Units (RUs). Remedial Units are categorized in two tiers: Tier I (RU1s) for vessels that meet the base target, and Tier II (RU2s) for those that do not.

Non-compliant vessels may offset their Tier II Remedial Units by acquiring Surplus Units from compliant vessels.

Key findings from Rystad Energy’s research reveal a complex interplay between SUs and RUs within the framework. Initial projections show SUs starting at 40 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent in 2028, growing to 53 million tonnes by 2035. Simultaneously, RU2s are expected to increase significantly from 47 million tonnes to 234 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent annually by 2035. The availability ratio between the SUs and RU2s will effectively set the market-clearing price for exchanges, with Rystad Energy’s projections suggesting that demand for RU2 offsets will consistently outstrip SU supply until 2035. This supply-demand imbalance will likely drive SU trading prices close to the Tier II penalty threshold.

“Our analysis indicates that the trading price of surplus units will likely be governed by market dynamics rather than biofuel cost premiums,” said Yu. “Given the limited availability of advanced biofuels for shipping, we anticipate that SU prices will approach the Tier II penalty level of $380 per tonne of CO2 equivalent, minus transaction costs.”

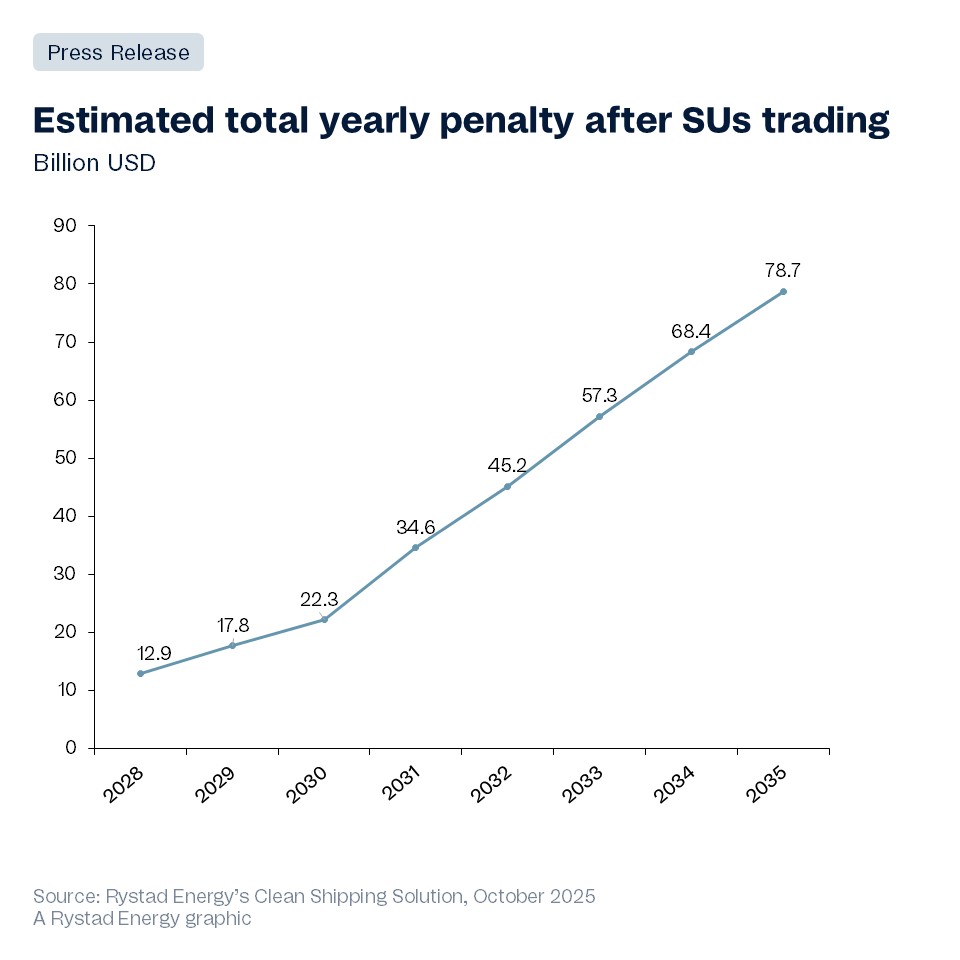

While surplus units will substantially offset Tier II penalties through 2030, this mechanism could inadvertently limit the financial incentives available for early adopters of zero-emission technologies. The real turning point comes in 2031, when surplus units become increasingly scarce, compliance requirements tighten, and shipping companies face growing emission deficits. This will trigger a sharp escalation in penalty collections, substantially boosting the Net-Zero Fund’s capacity to support the industry’s decarbonization efforts.

The research highlights potential challenges in the framework’s design, particularly the two-year limit on banking surplus units to avoid dilution of future emission-reduction efforts, which could potentially dampen early adoption of clean technologies. This constraint stands in stark contrast to the FuelEU Maritime regulation’s permanent banking allowance.

Financial projections indicate substantial growth in the IMO Net-Zero Fund, with combined Tier I and Tier II penalties expected to generate approximately $13 billion in 2028, escalating to nearly $79 billion by 2035. However, our analysis raises concerns about the framework’s effectiveness in supporting the transition to zero-emission vessels, particularly in its early years.

Rystad Energy’s analysis estimates the potential reward level and benchmarks it against the required reward level, which is the threshold necessary to equalize the effective costs of e-fuels and conventional fuel oil. Initially, the required reward level is substantial due to the significant cost premium associated with e-fuels, resulting in a shortfall in cost compensation from the net-zero fund until 2030, even if 100% of the fund’s resources are allocated to rewards. However, as technological advancements drive cost reductions, learning eff