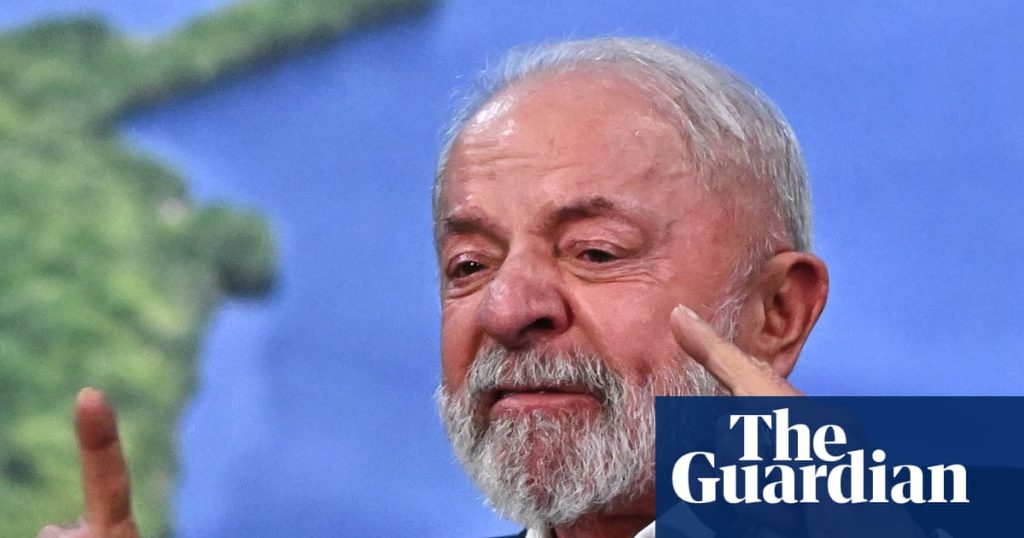

The Brazilian president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has told Cop30 delegates that he will take his fossil fuel transition roadmap to the G20 in Johannesburg this week to campaign for it, despite reports that petrostates have said they will not accept the plan.

Before leaving Cop30 in Belém, the figurehead of the global south told civil society representatives he was ready to fight for the proposal to phase out oil, coal and gas in whatever forum was necessary.

“Lula told me that he was all in on the roadmap and that he would campaign for it everywhere, in the G7 and G20,” said Marcio Astrini, director of the Climate Observatory campaign group. “It’s his proposal. He’s worried about those who are threatened by extreme climate events. That’s what moves him. He understands the climate crisis is a machine that worsens poverty and inequality.”

Climate conferences are always games of three-dimensional chess as the world’s governments juggle priorities and haggle over commitments. But the prospect of Lula opening a new front for his campaign in Johannesburg adds an intriguing transcontinental twist.

It would also lift the stakes. The G20 brings together more powerful world leaders than Cop, where negotiations are mainly conducted by ministers.

There is certainly a need for more impetus. Eighty-two governments signed up to the roadmap on Tuesday, but they only account for 7% of global fossil fuel production. The roadmap has since been knocked backwards, with sources close to the negotiations saying that Russia, China, India and South Africa jointly had told the Brazilian Cop presidency they would not accept the plan.

The “like-minded developing countries” grouping, which includes coal and oil producers, has also expressed reservations. As a result, the Guardian understands the proposal has been stripped out of the latest draft of the main negotiating text. Others claim the roadmap is already roadkill.

Nobody is entirely sure because the Brazilian presidency has gone into a secretive mode. Despite promising transparent “mutirão” collective negotiating, observers say the past day’s talks have mainly been behind closed doors with the hosts only showing portions of the text to each group of nations.

There may also still be room for manoeuvre. In private discussions outside the presidency’s meetings, sources say Saudi Arabian and Chinese diplomats have shown openness to the idea of a roadmap as long as each country can choose their own pathway. India has reportedly been more hesitant.

Less developed countries might also be persuaded to move if the European Union and other industrialised countries make a clearer commitment on finance. The EU has indicated that the roadmap is now a red line they are willing to defend, but they also have to be willing to pay.

Throwing an extra level of complexity into the mix are the divisions within Brazil, where Lula’s scope for action is limited by a powerful petrochemical and agribusiness lobby.

The planet’s most important stories. Get all the week’s environment news – the good, the bad and the essential

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain information about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. If you do not have an account, we will create a guest account for you on theguardian.com to send you this newsletter. You can complete full registration at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

after newsletter promotion

Different ministries within his government also have different levels of ambition for Cop30. The driving force until now has been Marina Silva, the environment minister, who persuaded Lula of the need for a roadmap and has pushed the idea in Belém. But the foreign ministry, represented by the Cop president, André Corrêa do Lago, is more cautious. Several sources told the Guardian they do not support the roadmap because of the risk of failure, and that they would rather focus on smaller, more easily achievable wins that could keep the multilateral process alive.

The next version of the negotiating text was expected late on Thursday, but plans were thrown into disarray early in the afternoon when a fire broke out in the pavilion area of the conference centre. Delegations holding meetings in their rooms nearby were evacuated but the UN said no one was hurt.

Firefighters controlled the blaze, but the entire venue had to be cleared from shortly after 2pm. The Guardian was told it was likely to be several hours at least before any delegates were allowed to return.

The incident disrupted a carefully choreographed series of meetings between the presidency and the main negotiating groups.

The Alliance of Small Island States (Aosis) had been scheduled to meet the presidency shortly before 4pm, but that was cancelled. The EU was due to hold a ministerial coordination meeting at 6pm prior to meeting the presidency at 9pm, but that timetable was thrown into doubt.

The severity of the disruption at this stage of the talks is likely to make it impossible to stick to the Brazilian timetable, and may push the talks well into overtime.