A wise saying goes, “He who wears the crown must bear its weight.” In India’s case, the crown is self-declared: the mantle of Vishwaguru, a teacher to the world. While Prime Minister Narendra Modi has boldly projected this global guru image in every multilateral summit and global forum, the realities at home and abroad tell a more tangled tale. Like all aspirations, this one too comes with its own contradictions, and India, at this moment, stands both on the cusp of greatness and at the edge of overreach.

The idea of India as a Vishwaguru is not new. It draws from a civilizational memory of Nalanda, Takshashila, the Upanishads, and a thousand years of philosophical inquiry. For centuries, India was indeed a source of intellectual, spiritual, and ethical influence. But nostalgia does not make policy. Today, India’s ambitions are being declared from podiums in New York, Paris, and Johannesburg, while its domestic terrain reveals far different stories: of curbed academic freedom, rising communal polarization, economic precarity, and a foreign policy swinging wildly between strategic autonomy and reluctant alignment. The cracks between projection and reality are growing too wide to ignore.

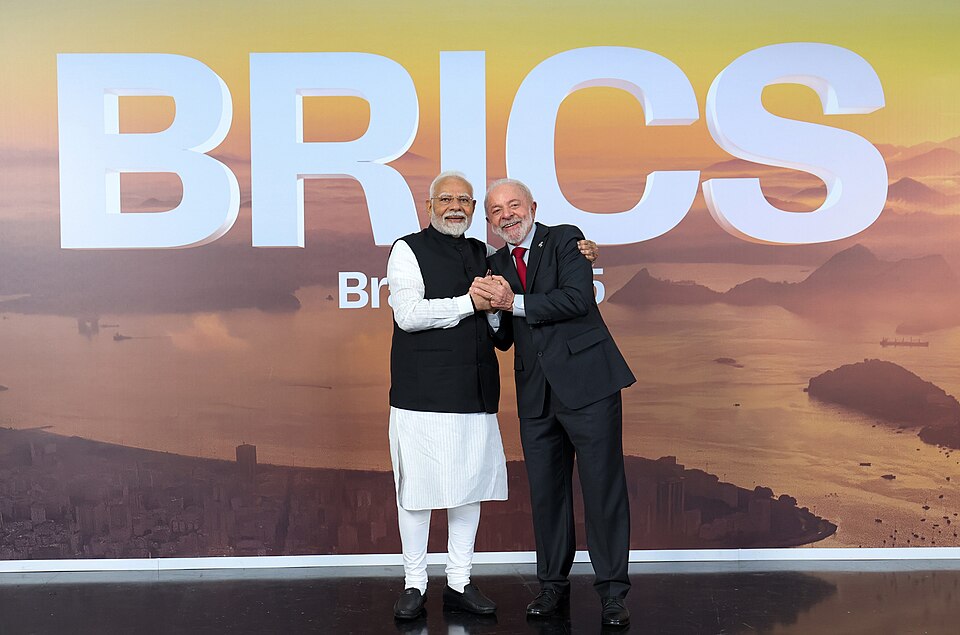

India’s foreign policy branding has taken on almost theatrical dimensions. Initiatives like Vaccine Maitri, its presidency of the G20, and repeated invocations of civilizational greatness are presented as proof of India’s new global stewardship. Indian diplomats speak of a multipolar world in which India plays the balancing pole. But what kind of balance is it, exactly? In Ukraine, India refused to condemn Russia’s invasion citing national interest, a term as elastic as it is convenient. In Africa, India competes with China through lines of credit and photo-ops but fails to match China’s infrastructural commitments. In Southeast Asia, it promises an “Act East” policy while still acting West. In the Gulf, it courts oil monarchies while internally stoking Islamophobia. The message is clear: India wants a seat at every table but resents being asked to bring substance.

Even its proudest moments like being dubbed “the pharmacy of the world” or hosting grand summits are double-edged. Behind the scenes are uncomfortable truths: vaccine shortages at home, record unemployment, a crumbling health infrastructure during COVID’s peak, and a bureaucracy too slow to match the scale of the ambitions being announced. Lofty statements from the government often serve as camouflage for institutional hollowness.

The Vishwaguru fantasy, however, is not only directed outward; it also serves a domestic purpose, creating a unifying myth of greatness at a time when fractures in the Indian polity are increasing. At home, the assertion of guru-hood often manifests in cultural supremacy. Textbooks are being rewritten, Mughal monuments erased from memory, and the English language vilified in favor of Sanskrit slogans. Universities, once bastions of diverse thought, are increasingly brought to heel. Scholars who challenge this narrative are branded “anti-national”. Media, mostly pliant, packages this as a cultural renaissance. But behind the fireworks, the quiet erosion of intellectual freedom continues.

Economic conditions are no less contradictory. While the government boasts of rising GDP numbers and increasing foreign investment, inequality is worsening. The formal sector remains unable to absorb the millions entering the job market each year. India’s youth, its supposed demographic dividend, is being increasingly drawn into ideologically charged campaigns, while their real grievances unemployment, poor education, rising living costs, remain unaddressed. Can a nation that cannot empower its own young truly claim to guide the globe?

And yet, the desire to be a Vishwaguru is not without merit. India does possess unique experiences: it has managed a diverse democracy with over a billion people, it has pioneered digital public infrastructure at scale, and it has taken early leadership in climate negotiations, often punching above its weight. These are real achievements. But leadership on the global stage cannot be built on contradictions. Credibility must be earned through consistency not crafted by optics and soft-focus propaganda.

Why then does India persist in this guru self-image? Because there is political capital in the performance. International prestige feeds domestic pride, and vice versa. The global posturing helps consolidate nationalist sentiment at home, while the domestic consolidation projects strength to the outside world. It is a feedback loop that sustains itself until, of course, the world stops listening or begins to push back.

That moment may not be far. India’s widening gap between aspiration and execution is becoming increasingly evident. In climate negotiations, the West is beginning to ask hard questions about coal. In trade, Europe has started invoking human rights clauses in pending agreements. Even once friendly neighbors like Bangladesh and Sri Lanka are beginning to question India’s inconsistent promises made and not kept, assistance offered and then delayed.

The irony is this: the more India shouts about its greatness, the less it seems prepared to do the difficult internal work of actually achieving it. The ancient Indian tradition it claims to represent of debate, plurality, ethical statecraft has been replaced by spectacle. But the world today is not looking for teachers in saffron robes; it is looking for stable partners, transparent institutions, and societies that can self-correct. In that arena, India’s credentials are still unproven.

So, where does this leave us? Somewhere between performance and potential. India is still one of the few global actors with the scale and credibility to shape the 21st century. But to do so, it must go beyond the headlines. The Vishwaguru mantle is not just a crown; it is a mirror. And what India sees in that mirror, at this moment, is more a projection than a reflection.

And as we list our hopes and warnings, it is almost certain that, today, in Washington, Beijing, and even Dubai, they are not raising toasts, but taking notes measuring India’s words against its will, its promises against its policies, and most importantly, its guru complex against its governance reality.

[Image credit: Prime Minister’s Office (GODL-India), GODL-India, via Wikimedia Commons]

Arman Ahmed is the founder and president of DhakaThinks, Bangladesh’s first youth-led think tank, and a research analyst at the Nicholas Spykman International Center for Geopolitical Analysis. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect TGP’s editorial stance.