Today, most plants rely on solvent-based systems that absorb CO2, but these setups use a lot of heat, require major infrastructure, and can be costly to run.

A smaller, electricity-driven alternative is what the field calls a “membrane” system. A membrane works like an ultra-fine filter that lets certain gases slip through more easily than others, separating CO2 from the rest of the flue gas. The problem is that many membranes lose efficiency when CO2 levels are low, which is common in natural-gas plants, and this limits where they can be used.

A new study at EPFL has now analyzed how a new membrane material, pyridinic-graphene, could work at scale. This is a single-layer graphene sheet with tiny pores that favour CO2 over other gases. The researchers combined experimental performance data with modelling tools that simulate real operating conditions, such as energy use and gas flow. They also explored a wide range of cost scenarios to see how the material might behave once deployed in commercial plants.

The study was led by Marina Micari and Kumar Varoon Agrawal who holds the Gaznat Chair in Advanced Separations at EPFL. It is published in Nature Sustainability, and builds on the group’s previous research in developing scalable graphene membranes.

“As we are scaling up the technology, it is important to understand the implications on reduction on energy use and cost of carbon capture in the diverse sector of carbon capture,” said Agrawal. “This work address this.”

=

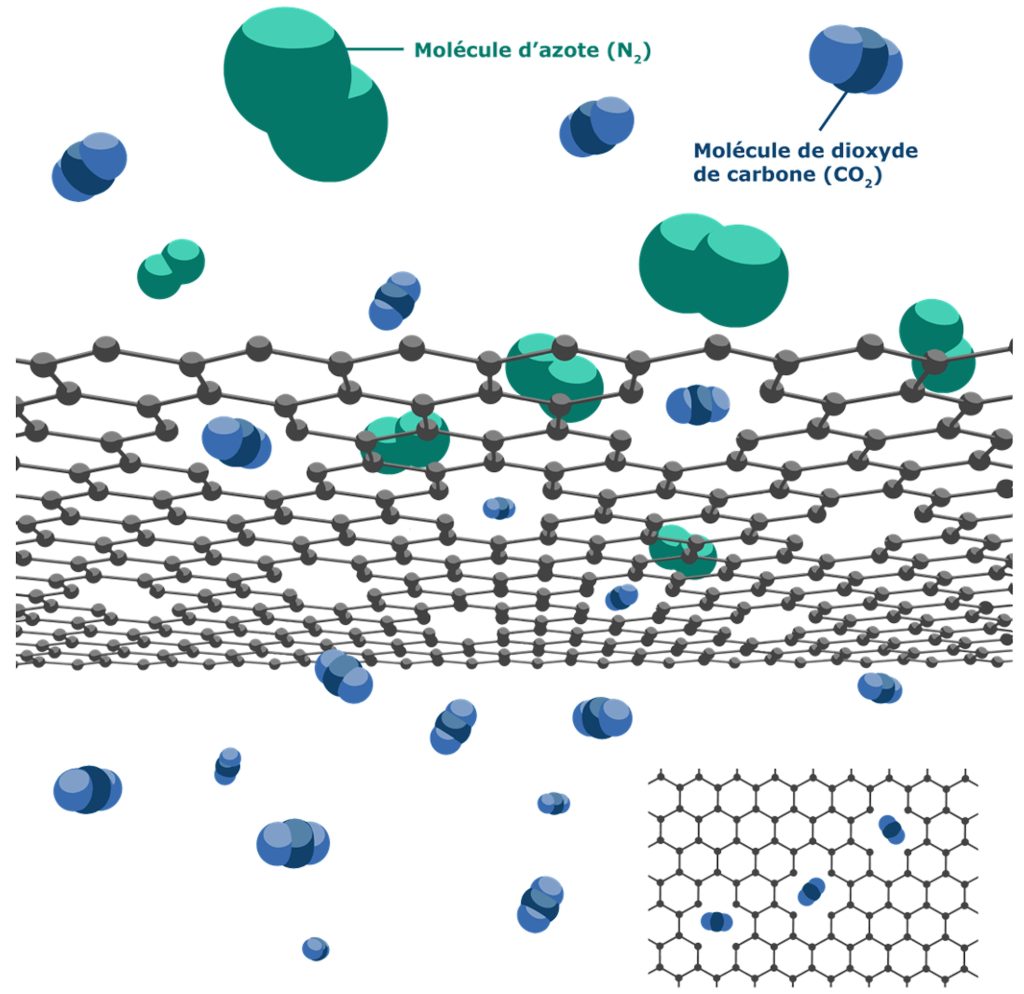

An illustration of the graphene membrane separating CO2 from N2. Credit: Ivan Savicev, EPFL

Modeling shows where the membrane performs best

The team tested different graphene-based membranes, including the pyridinic-graphene membrane, under several plant setups to compare how they would perform in real conditions. For natural-gas power stations, a three-step system that starts by enriching the CO2 stream reached promising costs, roughly USD 80–100 per ton, with best cases down to USD 60–80. This is noteworthy because membranes usually struggle with such dilute flue gas.

In coal plants, where CO2 levels are higher, the membrane’s strong CO2/N2 selectivity cuts energy use and brings costs into the USD 25–50 per-ton range. Cement plants have more oxygen in their flue gas, which makes selectivity trickier, but the membrane still reaches similar cost ranges and stays stable across the different scenarios tested. Across all three sectors, the membrane’s high permeance keeps the required surface area small, which helps reduce the footprint of a full capture system.

The study shows that pyridinic-graphene could offer a compact and potentially cost-effective alternative to solvent-based capture once scaled. It also points to areas where the material could still improve, especially its ability to distinguish CO2 from oxygen in cement flue gas.