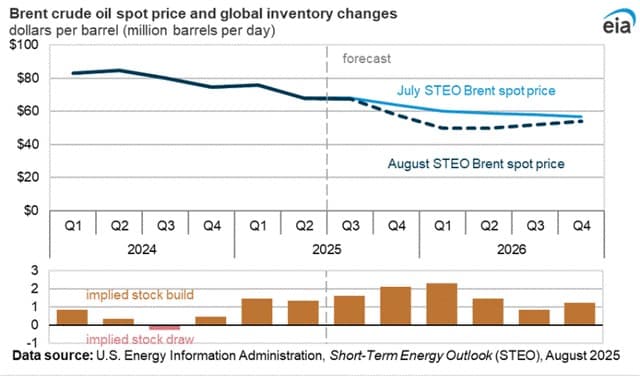

Despite providing most of the growth in global supply over the last decade or so, U.S. shale producers are subject to the effects of the whims of OPEC+, and Saudi Arabia in particular. Their decision to rapidly unwind previous output cuts has put over 2 mm BOPD on the market in a very short period, and resulted in a global stock build that’s just knocked the stuffing out of oil prices. We’ve seen this movie before and it always ends up in the same place. A big “lake” of oil that takes a year or so to work off, and as traders adopt a posture that they can get that marginal barrel anytime they want, prices plunge.

What goes down, eventually goes up and we have seen producers curtail activity, both onshore and offshore to conserve capital for the turnaround. Commodity prices are not the only driver for a decline in E&P activity.

Cost of supply and productivity also play a role in a company’s decision to allocate capex for increased drilling. If history is any guide we are in a bottoming phase for oil prices from these two aspects. This is not to say prices can’t decline further; of course they can. That said, the underlying factors that drive production growth or decline-cost of supply and well productivity, are shaping up to potentially deliver higher oil prices in the near future, in our estimation.

If history is any guide, we are in a bottoming phase for oil prices. This is not to say they can’t decline further, of course they can. That said, the underlying factors that drive production growth or decline-cost of supply and well productivity, are shaping up to potentially deliver higher oil prices in the near future.

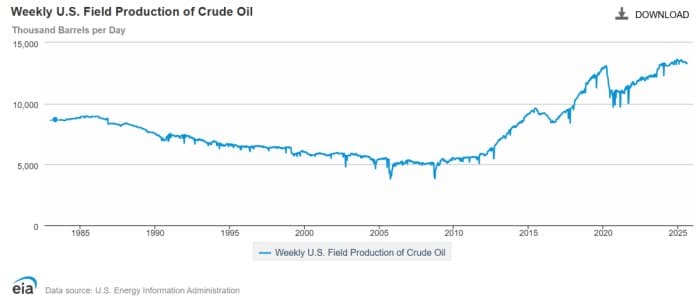

There are a lot of factors influencing shale output as we race toward the latter third of 2025. It is undeniable that we have seen a leveling off and perhaps a decline in oil output as noted in the Weekly Field Production of Crude Oil published by the EIA. As of the last data point on Aug 8th, U.S. total output was 13,327 BOPD. This is a 2% decline from the peak reported on December 13th, 2024, of 13,604 BOPD. The EIA chart below takes all sources into account, but at over 9.6 mm BOPD from the five largest oil-producing states – Texas, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Utah, shale liquids are the biggest component, as noted in last month’s EIA-914 (with data through May).

It should be noted that I am citing two separate EIA reports, and there can be a little “noise” between them.

What can’t be disputed is that the relentless growth in U.S. daily production has come to an end. The “Why” is subject to discussion. You can take your pick – low oil prices from oversupply, falling oilfield activity, a decline in Tier I drilling locations, technological gains, E&P M&A, or tariff tremors. All can play a role in crude price gyrations.

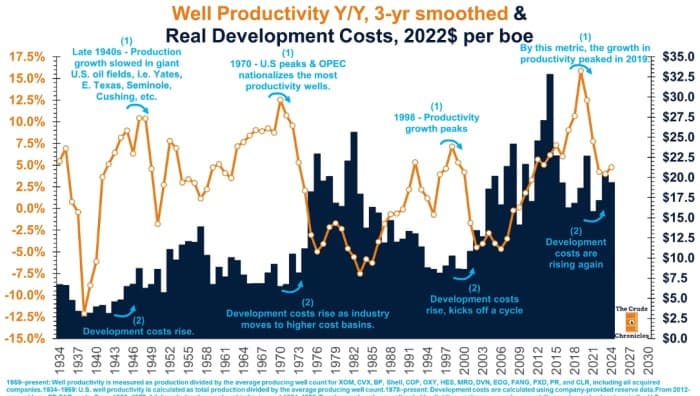

Something that isn’t discussed a lot and is the thesis for this article, very simply, costs are rising for the biggest contributor to U.S. liquids production-shale, and well productivity is declining. Rob Connors of The Crude Chronicles has published research, as shown in the chart below, that suggests an inflection from these two sources has occurred and is not yet represented in the price outlook for crude oil. Connors commented for this article:

“In 2024, well productivity (boe output per producing well) among the largest publicly traded non-OPEC producers rose just 3%—marking one of the slowest annual growth rates in the past 14 years, despite record production volumes.

History has shown that when well productivity growth begins to decelerate, non-OPEC producers are forced to move up the cost curve—developing higher-cost basins to maintain output. That shift in marginal supply economics puts upward pressure on prices, especially when demand remains stable or rising.”

Put simply the increased cost to develop these reserves necessitates prices that will support this activity, or it won’t happen.

Technology has led to a slight bump in productivity over the last four years as companies radically rethought their approach to horizontal drilling and completions. Lateral sections are now routinely over 10,000’ in key plays, and one result of the Upstream M&A frenzy of the last several years has seen 12,000’ laterals make up an increasing share of total wells drilled. 15,000’ laterals are also being done with some regularity. Clay Gaspar, CEO of Devon Energy, (NYSE:DVN) commented at an investor conference on the impact of longer lateral sections-

“How many dollars are we’re putting in to drill the same number of wells or maybe even more importantly, the same number of lateral feet? And so as we’re drilling longer laterals and there’s a lot of innovation in that space, that accrues to the bottom line, if we can get 4 miles of lateral delivering production, in one fell swoop, that’s just more capitally efficient. So that’s a great thing.”

Other innovations include increasing the number of stages in a frac to place more sand in the reservoir, AI analysis to improve the pumping operation, placing more sand deeper into the reservoir-contacting more rock and essentially turning lower quality rock into higher quality rock.

Opinions vary on how far technology can stretch to maintain oil output at current levels. The CEO of Chevron (NYSE:CVX), Mike Wirth, has noted that its main shale play, the Permian Basin, can be maintained at scale for many years to come. Others are less confident. The former CEO of Diamondback Energy (NYSE:FANG), Travis Stice, commented in an investor call that, “production has peaked and will begin to decline this quarter.” It is certainly not our place to say which of these energy titans is correct, but as we’ve noted above, U.S. output has declined by several hundred thousand barrels per day this year.

Your takeaway

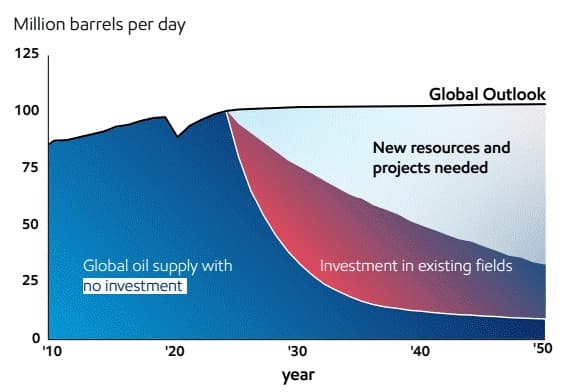

ExxonMobil (XOM) publishes a robust energy outlook every year. Here is a neat graphic from its current report showing the investment required to keep global production at current levels through 2050.

If you’re like me and see a gap between current projects planned and what’s needed to avoid energy poverty, not that far down the road, then you should feel better about the upstream energy sector. I think it has a bright future, no matter how muddy the current noise in the market obscures the reality. The current glut is an interlude, and better times lie ahead for these companies.

By David Messler for Oilprice.com

More Top Reads From Oilprice.com