Since its launch in 2013, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has emerged as one of the most ambitious development strategies in modern history. With $1.2 trillion invested across 147 countries, China has built an expansive network of trade routes, energy projects, and infrastructure, transforming connectivity across much of the Global South.

Kazakhstan has been a key BRI partner. Chinese investment in the country falls into three categories: 1) transportation and logistics, such as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), which is a key multimodal, road and rail route, connecting China to Europe via Kazakhstan, 2) oil and gas, and energy projects, and 3) other economic development projects. In total, China has invested in over 200 projects in Kazakhstan: China’s investment reached $25.3 billion over the period from 2005-2023.[1] In 2024, bilateral trade peaked at $44 billion, accounting for 45% of the $97 billion China-Central Asia trade volume.

At its inception, the BRI was centered on connectivity to facilitate trade through large-scale infrastructure projects. The focus of the BRI then shifted in 2023 from a quantitative approach to a more qualitative, ‘software’-oriented focus, expanding into diverse areas such as educational initiatives, clean energy, public health, poverty reduction, and artificial intelligence.

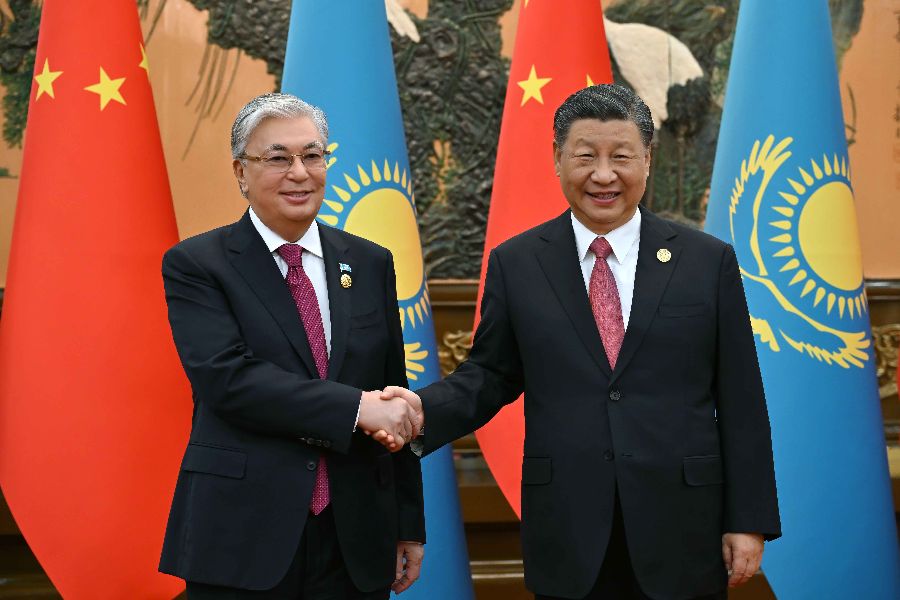

For instance, on June 16-18, 2025, at the second China-Central Asia Summit in Astana, China and Kazakhstan signed 58 new agreements worth $25 billion, bringing total Chinese investments to $50 billion.[2] The new agreements foster collaboration in key sectors such as green energy, agriculture, and infrastructure. Major deals include access to China’s Green Technology Bank, construction of a $2 billion coal gasification plant, a pumped storage power plant in Almaty, and large-scale agricultural processing projects in Zhambyl and Akmola regions.[3] The agreements included the establishment of three new cooperation centers for 1) poverty reduction, 2) education exchanges, and 3) desertification control, illustrating Beijing’s use of development assistance, knowledge-sharing, and cultural engagement to enhance its attractiveness – the core of soft power. Simultaneously, the establishment of 1) a cooperation platform for smooth trade, 2) signing the Treaty on Eternal Good-Neighborliness, and 3) issuing the Astana Declaration on joint security pledges, demonstrates China’s growing assertiveness and hard power presence under the guise of regional stability.

Despite these notable advancements in hard power, China’s soft power remains limited. As Joseph Nye defines it, soft power is the ability to shape preferences through culture, political values and ideals, and foreign policy – rather than coercion or payment. In Central Asia, China’s growing economic role has not translated into trust, admiration, or influence.[4]

Geopolitical landscape dynamics

This comes at a time of historic geopolitical transition. China now has a window of opportunity to position itself as a leading model of development, especially in regions like Central Asia that are recalibrating their foreign alignments. Three critical strategic variables will shape the geopolitical landscape in Central Asia.

Russia’s protracted war in Ukraine has severely damaged its economy and global standing. International sanctions, battlefield losses, and growing isolation have weakened Moscow’s ability to project influence in its former Soviet periphery. As Russia becomes more dependent on Beijing, China’s footprint in Central Asia continues to grow.

Second, Central Asian states – especially Kazakhstan – have distanced themselves from Moscow to assert their sovereignty. President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev’s public refusal to recognize the independence of Luhansk and Donetsk symbolized Kazakhstan’s commitment to international law and a multi-vector foreign policy, originally pursued by former President Nursultan Nazarbayev.

Third, under Donald Trump, U.S. foreign policy has shifted toward transactionalism and strategic retrenchment. Its waning presence in multilateral diplomacy creates space for China to position itself as a more engaged global leader – particularly in the Global South and Eurasia.

Opportunities and challenges

These changing geopolitical dynamics provide China with a golden opportunity to offer a viable alternative, positioning itself as the global leader, especially in the Global South, Central Asia and Kazakhstan. In 2025, China must navigate complex pressures at home and abroad. Overcoming these challenges will require visionary global leadership, a commitment to building a new multilateral order, and an audacious, forward-looking strategy.

Domestically, China faces a number of challenges, including its dependence on an export-driven model, an aging and shrinking population, and stagnation in the real estate sector. To alleviate internal pressure, China’s economic development model should transform into an inclusive market-based economic model, better integrated with the world economy.

Second, China’s failure to make soft power gains stem not from lack of investment but from persistent negative perceptions. Despite massive infrastructure spending, public sentiment in Central Asia remains wary. Concerns include authoritarianism, human rights abuses in Xinjiang, debt trap diplomacy, and land acquisitions. Beijing’s promises of mutual benefit are undermined by its authoritarian practices at home. Without addressing these contradictions, China is unlikely to earn genuine trust or long-term influence.

Strategically distancing itself from Russia will be crucial. By doing so, China can solidify its partnership with Central Asian states, as symbolized by the Xi’an Declaration signed on May 19, 2023, and the Treaty on Eternal Neighborliness, signed in Astana on June 18, 2025.

China should not only effectively counter containment efforts exerted by the U.S., but also embrace new allies and partnerships, including reinforcing its ties with Central Asia as an emerging regional and global player. It can do so through the development of educational and cultural exchanges. For instance, KIMEP University has over 30 agreements with Chinese universities and research institutions, including with Peking University, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), and Tsinghua University.

The shifting landscape in Central Asia presents both opportunity and risk for China. With Russia weakened, U.S. influence in retreat, and Kazakhstan pursuing balanced diplomacy, Beijing has an opportunity to expand its footprint. But success depends on balancing economic engagement with political sensitivity – fostering local development, respecting sovereignty, and avoiding perceptions of coercion. Infrastructure and trade alone do not guarantee influence. Without greater transparency, accountability, and alignment between its actions and values, China will continue to face limits to its soft power – no matter how extensive its economic reach.

[Photo by akorda.kz]

Dr. Chan Young Bang is the founder and President of KIMEP University, Principal Investigator at the DPRK Strategic Research Center, and a former economic adviser to Nursultan Nazarbayev, the first President of Kazakhstan. His current research focuses on nuclear non-proliferation and the economic development of the DPRK (North Korea). He is the author of more than 65 articles and nine books on the global prospects for achieving peace and prosperity on the Korean peninsula. His latest English-language books include Transition Beyond Denuclearization: A Bold Challenge for Kim Jong Un and A Korean Peninsula Free of Nuclear Weapons: Perspectives on Socioeconomic Development which were published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2020 and 2023, respectively.

Dr. Anar Shaikenova is a senior researcher in the DPRK Strategic Research Center at KIMEP University, Kazakhstan, and an assistant professor in the Department of Public Administration. Before joining the Ph.D. program, she worked with USAID, the Asian Development Bank and the U.S. Department of State EXBS Program on strategic trade controls in Kazakhstan and in the Central Asian region. Dr Shaikenova has a Ph.D. in public policy from Nazarbayev University and an MA in public administration from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, U.S.

References

[1] Yingshi, Gao. 2024. “China-Kazakhstan Economic Cooperation Paving Way for Next Golden Thirty Years.” The Astana Times. Retrieved from https://astanatimes.com/2024/07/china-kazakhstan-economic-cooperation-paving-way-for-next-golden-thirty-years/.

[2] Huaxia. June 18, 2025. “Key takeaways from 2nd China-Central Asia Summit in Astana.” Xinhua News Agency. https://english.news.cn/20250618/1569680311d94cbf96db8722c5538747/c.html.

[3] “Kazakhstan, China Sign Several Strategic Agreements Ahead of Second China-Central Asia Summit.” June 17, 2025. The Astana Times. Retrieved from https://astanatimes.com/2025/06/kazakhstan-china-sign-several-strategic-agreements-ahead-of-second-china-central-asia-summit/.

[4] Joseph S. Nye,“Soft Power”, Foreign Policy, Autumn, 1990, No.80. p.155.